By Dr. Ray Ochs

Vice President of Training Systems for the Motorcycle Safety Foundation

I was a chubby little kid who liked playing baseball and pinball machines while drinking 3V Cola. (3V stood for vim, vigor, and vitality, but I think it was mostly sugar!) But in my teens, something happened — motorcycles entered my life. And over decades of work (and fun), I developed my personal 3Vs: vision, vectors, and values. Vision to make a positive difference with character and competence. Vectors to point in the right direction with an appropriate intensity and balance. Values related to the quality of life, including what safe and responsible motorcycling means.

It was the mid-60s when it happened. I was a teenager and was offered a ride as a passenger on a Honda Dream 305. We cruised through the parkways of St. Joseph, Missouri, on a humid summer evening. It felt perfect. The sensation of freedom, aliveness, and interaction with nature was overwhelming. I knew then that motorcycling would be a part of my adult life. Little did I know what that would lead to.

My first real street ride as an operator was a red Suzuki 50cc “noped” with step-through design and all the power I needed. (Up to 28 mph!) My brother won it in a raffle and didn’t want anything to do with it. So I gladly hopped on as an excited 18-year-old with not a lot of safety sense, but I did wear a helmet and had no incidents. Many a day was spent riding country backroads to enjoy the openness, freedom, and visceral sensations.

Several years later, having finished a master’s degree in Health and Safety from Indiana State University in 1972, I worked (and studied) at one of the first traffic safety centers in the country. It was called the Driver and Traffic Safety Education Instructional Demonstration Center, and I worked under a notable professional, Dr. Walter Gray. Part of the center’s activity was to offer a motorcycle training and education course for undergraduate students desiring certification to become a high school driver-education teacher. We rode around a driving range for hours on small training bikes, not knowing the creation of the Motorcycle Safety Foundation was just around the corner.

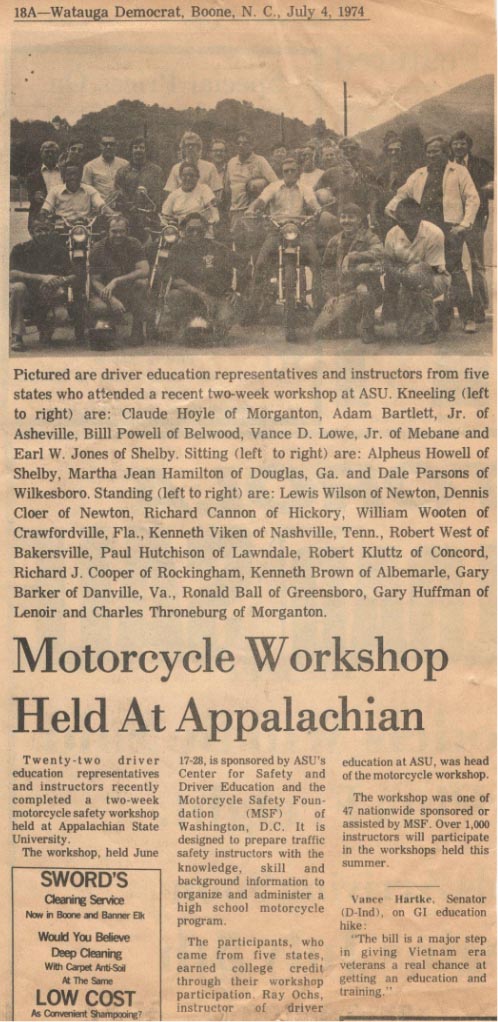

I took those experiences to my first full-time university position at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. I was responsible for teacher preparation certification processes, working alongside Drs. Charles McDaniel and Harry McDonald.

As a junior faculty member, I was called to duty to participate in this “new MSF thing” being sponsored by Kawasaki in Keene, New Hampshire. I remember it well because my luggage didn’t make the trip and I showed up in a sport coat, on a dark and dreary day, for classroom and riding. Of course I didn’t ride. A vivid memory is how impressed I was with one of the facilitators: Dr. Duane Johnson from a university in Illinois. His soft, nurturing, and humorous approach made a lot of friends for motorcyclist safety. Of note is that many faculty members at traffic safety centers in Illinois were busy studying, researching, and developing similar programs that would become a foundation for early MSF curricula.

Not long after that in 1973, the Motorcycle Safety Foundation was officially established, and MSF invited university professors who were at traffic safety centers around the country to a certification course. It was held at the University of Maryland in College Park. They had a very large driving range, and at one time there were over 30 motorcycles interacting in a traffic mix pattern on their range.

A unique experience was to have participants take turns driving a car within the pattern, which was highly stressful because you didn’t want to miss seeing any riders in all those blind spots. The course focused on how motorcycles worked, and how to teach high school driver-education teachers to implement rider education in high schools. This was patterned after driver education, which was offered in nearly every high school in the country. Since driver-education teachers had the fundamental knowledge of driver safety, all they would need to do is learn to ride if they didn’t already. When that didn’t work out very well, it didn’t take long for MSF to switch from teaching teachers how to ride to teaching riders how to teach. It was clear that to have a successful motorcyclist safety program, potential instructors must have an innate passion for motorcycling.

Of course, anyone teaching motorcyclist safety had to own a motorcycle. I picked up a new 1973 red-and-white Honda CL350 Street Scrambler. Most of my riding was cruising around on the Blue Ridge Parkway between Boone and Blowing Rock in North Carolina. The first long ride I took (a whole 60 miles round trip!) left my muscles buzzing from the twin-cylinder vibration, something that I did not anticipate. Also, I joined the American Motorcyclist Association and remain a lifetime member.

While at Appalachian State, I recall we had a special visitor during the summer of 1973. It was Dr. Charles Hartman, the first president of the Motorcycle Safety Foundation. As a demonstration of what could be skill development exercises, I led a group of driver-education teachers around the university’s four-acre driving range through a variety of traffic mazes consisting of hundreds of traffic cones. I narrated the activities via a wireless PA system carried around my shoulder. I remember stating as a summary: “The variety of skill development exercises can be left to an instructor’s imagination,” or something similar. I mean, that was over 50 years ago. Of course, I was just trying to avoid embarrassing myself in front of the dignitaries who were observing.

After two years at ASU, I took advantage of an opportunity to move from the mountains (riding season was too short) to the flat, sandy area (long summers) of North Carolina, namely East Carolina University in Greenville. The traffic safety program director, Dr. Al King, had already established a one-semester course in motorcycle safety, and I quickly took the reins to solidify the program. A unique feature of ECU’s program was that they had no driving range. We completed most of the training in a large field next to the football stadium, and after learning the fundamentals, we rode simple trail areas across from the university. By the way, this was done on street motorcycles, mostly Honda CB125s.

It was 1976 when I accepted a tenure-track assistant professor position at Eastern Kentucky University in Richmond. It was a large regional university and housed the Traffic Safety Institute. Although my position was focused on driver-education teacher preparation certification, I established a three-semester-hour credit course titled “Beginning Motorcycle Safety.” My ride was now a yellow Honda CB750 Four Super Sport, and the first long distance ride included a venture south to Deal’s Gap and the Blue Ridge Parkway, where I got my first exposure to the effects of wind-chill factor. The initial centerpiece of the university course was the MSF Motorcycle Rider Course (MRC) and later the Motorcycle RiderCourse: Riding and Street Skills (MRC:RSS) in 1986. The course became so popular that we quickly added more sessions. It became one of the university’s most popular “restricted electives.”

In 1980, MSF had to start recruiting instructor-trainers due to the proliferation of motorcycle safety programs. Staff could not keep up with the demand for instructors as states began funding formal rider education programs. I was tapped to acquire the “Chief Instructor” credential.

After completing the course at MSF’s then-headquarters in Linthicum, Maryland, under the tutelage of MSF staffers Andy Krajewski and Ted Unland, I began teaching MSF Instructor Preparation Courses in several states. I did quite a bit of work for Meredith “Hoot” Gibson, who was the MSF eastern region manager in Knoxville, Tennessee. I also conducted several Instructor Preparation Courses for the North Carolina program. My motorcycle at that time was a 1980 Suzuki GS850, and a few years later, a 1983 Honda Gold Wing Interstate.

The late 1980s saw the growth in powersports sales and incidents in the all-terrain-vehicle world. The industry and federal government worked out the Final Consent Decree that stopped three-wheel ATV production and led to the establishment of a national training program. I was contracted by the newly formed ATV Safety Institute to help craft an instructional program. I took a leave from the university to spend one year at ASI’s Southern California offices to work on the basic curriculum and the Instructor and Chief Instructor materials.

Then in the early 1990s, MSF needed help in redesigning its Chief Instructor program. I was hired to develop and test a new approach to MSF trainer-training. (I guess they liked the work I did for ASI.) MSF employees Beth Weaver and Ron Shepard facilitated program development, and many Chief Instructors from around the country helped along the way. After spending the summer at MSF headquarters and traveling for pilot- and field-testing, the Chief Instructor Guide was released a few months later. Motorcycles I was lucky to own during those years included a 1993 BMW K75, a 1997 Harley-Davidson 1200 Custom Sportster, and later back to a 1997 Honda Gold Wing. Since then, a Gold Wing has always been in my garage. My favorite journey during those years was to cruise down to the Blue Ridge Parkway via Gatlinburg, Deal’s Gap (of course), and then Cherokee to Boone, North Carolina, and back home to Kentucky.

Fast forward to the mid-1990s when new leadership took the helm at MSF. Tim Buche was named president and he established a team to move MSF rider education and training into the modern era. The group was named Rider Education and Training System Development and Oversight Team (RETSDOT). I was one of 13 charter members, and the group eventually had over 50 individuals participating in moving MSF catalog from a few courses to a complete lifelong learning framework with multiple RiderCourses. This included a sea change in methodology from content-centric processes to a learner-centered approach, and a deep dive into the underpinnings of safety education, adult and accelerated learning, and motor skill development principles.

In the early 2000s, I divided time between EKU’s Traffic Safety Institute, field-testing a new learn-to-ride course (the Basic RiderCourse or BRC) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and meeting at MSF headquarters in Irvine, California, for RETSDOT interaction, which included RiderCoach certification processes and fleshing out a complete Rider Education and Training System. At the time, I was serving as Acting Director of MSF Training Systems. Nearing retirement at EKU, I transitioned to full-time work at the MSF in 2002. Oh, and I finished up a doctorate at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, in educational psychology with emphasis in adult learning, earning an “Outstanding Achievement in Adult Education” certificate. The move to Southern California allowed me to commute to work by motorcycle pretty much daily. My new tour routine was an annual triangular trek through Sequoia National Park, Yosemite National Park, and returning via the Big Sur back home to Orange County. In 2012, I was fortunate to earn the State Motorcycle Safety Association Chairperson’s Award.

Today, I remain busy with all things motorcyclist safety, with most of my time devoted to developing and testing programs that could benefit riders and their safety. This includes certification and development of RiderCoaches, RiderCoach Trainers, and Quality Assurance Specialists. I also received the 2023 State Motorcycle Safety Association Outstanding Contribution Award. I’m blessed to be surrounded by dedicated and competent staff and support, which of course includes my wife Carolyn.

I remain optimistic for the future of MSF’s programs and activities, and appreciate its noble mission in the pursuit of motorcyclist safety. I also maintain a strong belief in the value of rider education and training. I think that through MSF, rider education and training is doing as much as reasonably possible within its resources and national priorities to contribute to the federal Safe System Approach and Zero Fatality initiatives.

I’m forever thankful for the opportunities that have come my way, and my appreciation will never end. I’m eager to continue to offer contributions that may make a positive difference in the lives of those who make motorcycling part of their lives. I remain grateful for the work that MSF staff, RiderCoaches, RiderCoach Trainers, Quality Assurance Specialists, and program administrators have done in the name of motorcyclist safety. A heartfelt thanks to all of you and to MSF! I hope to see you out there.

Dr. Raymond Joseph Ochs is Vice President of Training Systems for the Motorcycle Safety Foundation, where he is responsible for course development, RiderCoach certification, and quality assurance. He became an MSF-certified Instructor in 1973 and a Chief Instructor in 1980. He joined MSF staff full time in 2002.