By Corey Seymour

Senior Editor, Vogue. Author of Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson

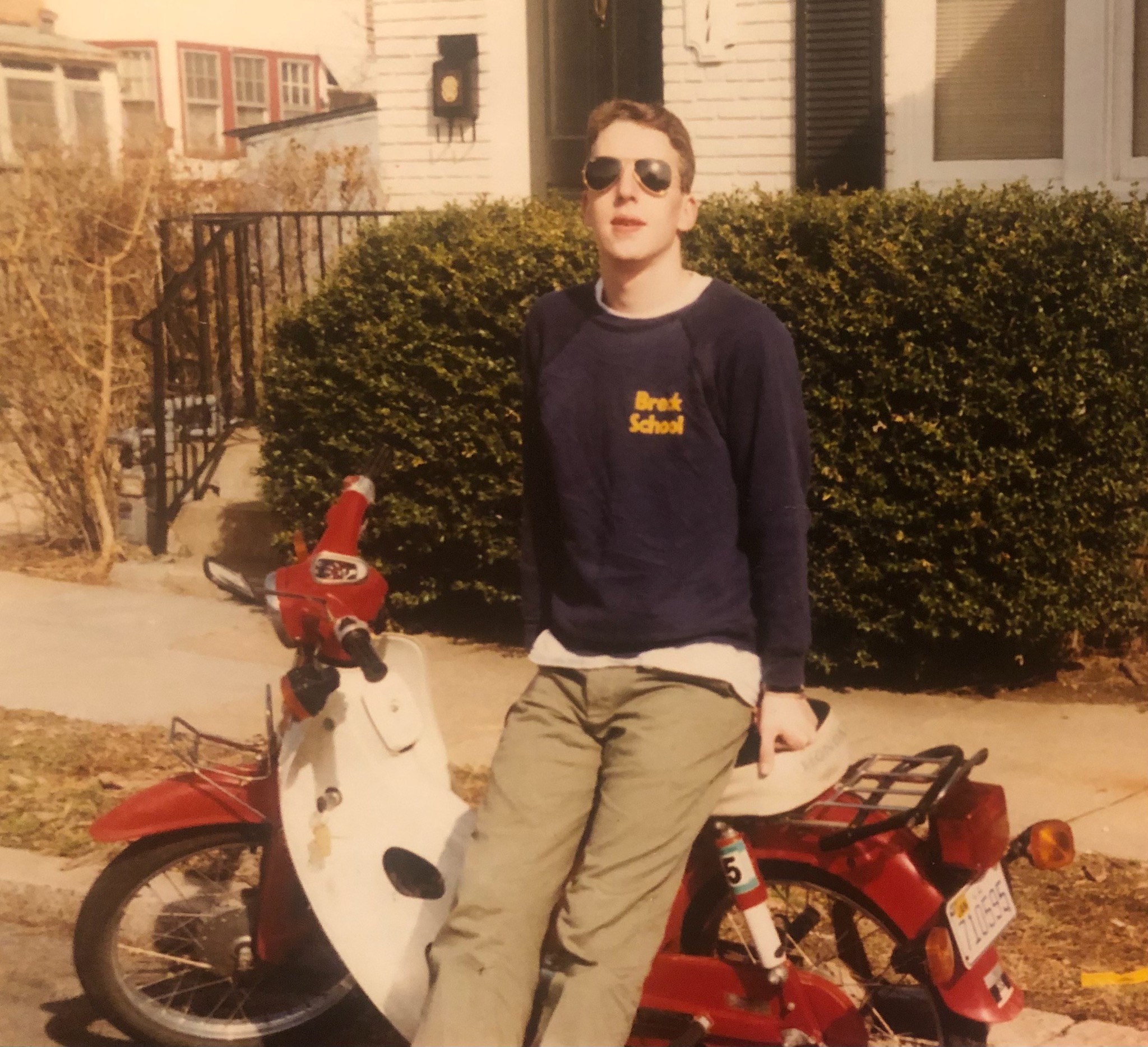

I entered the world of motorcycling as the unwitting victim of what, in retrospect, was a kind of scam. Decades ago, in the fourth-floor hallway of Copley Hall, my dorm at Georgetown University, a casual friend a couple years ahead of me was graduating and needed to unload his Honda Passport (aka Super Cub). Easily playing to both my naïveté and my weakness, he presented the whole scenario to me as a kind of romantic, dashing notion à la Evelyn Waugh in wartime, Brideshead Revisited on wheels. (We were English majors—it made a kind of bent sense at the time.) With almost no discussion, I gave my friend a few hundred bucks without having so much as eyeballed the bike, he gave me a key and a white helmet, and we shook hands.

Never mind that the thing puffed out its chest with a mere 70 cubic centimeters of engine. (Forget about harnessing horsepower—this was more akin to harnessing a team of miniature schnauzers to climb the Continental Divide.) That little red bike was instant fun, instant freedom, and instant thrills: No longer a kind of passive victim of the vagaries of bus and subway schedules, I was now untethered and off the grid, exploring the entirety of Washington, D.C., and peeking into northern Virginia and suburban Maryland, 43 mild-mannered miles-an-hour at a time. (I swear I got the thing up to 50 at least once. Swear.)

Unfortunately, those good times ended one day with an instant trip to a local jail cell: One moment I was standing inside the rotunda of the Jefferson Memorial reading about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; the next moment, speeding (well, let’s say rolling) out of the nearby parking lot, a police officer waved me to the side of the road.

About the rest I can only plead half-innocence. My friend had been charmingly vague about notions like registration—mumbling something about buying the bike from a retired CIA agent in northern Virginia, in whose name it was still registered—and didn’t mention a thing about, you know, being licensed to pilot the thing. For my part, the Passport was so simple to operate that it seemed preposterous that a license might be required—but as for the Virginia plates hanging below the back seat? They seemed more ornamental than functional. (Chalk another entry up for the sheer number of things in the real world that I knew absolutely nothing about at this age.)

I produced for the officer’s benefit the hand-written bill of sale that Kevin had drawn up that day in the hallway, which stated something like “I hereby do bequeath this fine motor steed to my hale friend Corey Seymour for the princely sum of 400 American dollars.” Surely this would prove something?

Spoiler alert: It did no such thing, but after a backseat ride and a few harrowing minutes in a cell at a nearby police station, I was let go—ultimately with a mere slap on the wrist, but alas: While that episode effectively expired my Passport, I would never forget the sense of freedom and exhilaration it opened up.

Over the next couple of decades, the dream of motorcycling was much with me; the reality, less-so. Moving to Manhattan proved to be its own kind of high-speed adventure for quite some time, but eventually a kind of low-grade but persistent fever set in. Occasional rides—with three different friends in three different states over a number of years, but always, alas, on the back of a Triumph—did nothing but fan the flames. And it wasn’t just me. One night, over dinner in the city with a friend and his girlfriend, the friend finally confessed: “Just once I want that feeling of walking in some place, sidling up on a stool, and just setting my helmet down in front of me.” To which his girlfriend, so over this persistent fantasy, instantly replied: “Why don’t you just buy a helmet?”

Even my job seemed to be teasing me about the whole thing. As a young editor at Rolling Stone I wound up as an assistant to Hunter S. Thompson for a decade or so and soon found myself listening to his stories about playing chicken aboard a Vincent Black Shadow in San Francisco in the sixties, and about shadowing Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels before that. I helped him get his hands on a 1995 Ducati 900 Supersport SP to review—if that’s the word—for his infamous piece for Cycle World, “Song of the Sausage Creature,” for better or worse. (Better: The story is simply amazing, a must-read, out-loud if possible. Worse: My heart still goes out to the Ducati dealer in Palm Beach, Florida, who delivered his finely tuned state-of-the-art machine at the parking lot of The Breakers to a somewhat addled rider who, upon first firing up the motorcycle, nearly drove it into the nearest brick wall.) Years later, after Hunter died, I spent a couple years interviewing scores of his old friends and kindred spirits for a book—including Sonny, along with Hunter’s longtime landlord, who talked about riding Bultacos across the fields of their rancher neighbors outside of Aspen, Colorado.

At the end of the day, though, the same sad truth: No bike to call my own.

That all changed during the pandemic, when I finally executed the plan I’d been harboring in my head for so long: I signed up for Motorcycle Safety Foundation’s Basic RiderCourse on Staten Island, drove myself out there with a mixture of nerves and excitement, learned a ton, and got my license. Within weeks, I was riding a borrowed BMW G 310 R all over town and, soon enough, up the Palisades Parkway to Bear Mountain; within a month, I connected with another friend looking to offload another bike quickly before another move out of town. This time, though, the bike was an 865cc 2013 Triumph Bonneville T100. It went much faster than 43 mph, had shockingly few miles on it, and—be still my heart!—came with a title.

From this point on, my life changes. Let’s just call it what it is, yeah? It’s an obsession. I mean: How many casual motorcycle riders have you met—people who could take it or leave it, go for a ride now and again—versus the kind of rider who thinks, plans, dreams, schemes, and lives to ride?

I am in love; I am obsessed. If I’m not on the bike, either out on a highway or simply riding to work every day from Brooklyn to the World Trade Center—every pothole and blind intersection imprinted on my brain—I’m reading about the bike, I’m reading about other bikes, I’m watching YouTube videos about my bike and other bikes, I’m teaching myself how to fix and maintain my bike, I’m learning about the history and development of motorcycles, I’m buying and studying maps of where I’m going to ride my bike, I’m on message boards and Instagram pages about bikes and reading poetry about bikes. On a lucky day, I’m meeting people nearby who have bikes and we’re boring everybody else around us by disappearing into our own world of talking about bikes.

I soon found myself at the Royal Enfield Slide School in Dallas, learning from American Flat Track racer Johnny Lewis how to let that back wheel slide around corners and kick up serious dirt; I test-rode everything I could get my hands on, from Kawasaki sport bikes to BMW’s wondrously monstrous 1800cc R 18. I flew to Atlanta for MSF’s then-new AdventureBike RiderCourse. When my family traveled to California for a vacation last summer, I borrowed a Ducati Monster for sunrise jaunts up and down Highway 1, returning before everybody else woke up; when we all went to Paris the year before, a friend there lent me his LiveWire, and I spent spare moments and late nights traversing the city, from our hotel in the 16th near the Bois de Boulogne up and over to Sacré Coeur and back—along with a romantic spin with my wife, speeding silently along the Seine and through the Louvre and around the Eiffel Tower, something I shall never forget. When I came back, I found myself at the center of a kind of extracurricular project conceiving and executing a series of adventures around the world for a gonzo-inspired launch project for Harley-Davidson’s Pan America adventure bike. (I couldn’t hog the fun and do all the rides—but I did get to speed across the salt flats of southern Nevada before rolling back into Las Vegas just as night was settling amidst an epic thunderstorm.)

I could go on—but the fact that my eight-year-old son and eleven-year-old daughter have strong opinions about MotoGP riders Marc Marquez, Fabio Quarteraro, and Pecco Bagnaia might be the best canary in this particular coal mine. (As for my wife, I’ll say just this: Among her absolutely myriad talents, she knows about Valentino Rossi’s switch to Bridgestone tires in 2007.)

A few weeks ago, I was lucky enough to meet Giacomo Agostini, perhaps the best motorcycle racer of all-time, and through him I met Rob Ianucci, founder of Team Obsolete, which races his armada of legendary vintage racing bikes. (It’s Rob’s contention that motorcycles built to race should be, you know, raced.) I’m currently in the early stages of planning my visit to Austin for the MotoGP race there in April, and in the meantime still riding to work—barring snow, sleet, blinding rain, or freezing temperatures. (When the weather’s like that, I stay indoors, drawing up plans and story lineups for my dream motorcycle magazine.)

I’m also—after a few years spent modding it out, shining it up, and treating it right—cheating on my beloved Bonneville, sneaking out for test rides on a 2010 Ducati 848 for sale at a nearby dealer. It’s beautiful, and it’s fast—my new obsession and maybe, just maybe, my next fascination.

If I’m being honest, though, everything I love about riding—and everything I’m still chasing with that gorgeous new-old Ducati—was in that little Honda Passport decades ago. It’s still about getting off the grid, away from the subway, out from inside the car, whether I’m riding in the city or out on the blue highways with endless horizons. It’s about the visceral rush of going fast, yeah—but it’s also about responsibility, a learning curve, chasing the perfect line, the perfect lean. It’s turning a certain kind of fear into a certain kind of challenge, arming yourself with the knowledge and the experience and the focus you need, and coming out the other side both proud and calm.

For me, it’s also about knowing you’re never going to get there—perfection, total knowledge, whatever your particular holy grail—but being overjoyed, again and again and again, that you get to keep trying.