By Keith Dowdle

Contributing Editor at Cycle News Magazine

I first became aware of the Motorcycle Safety Foundation in late 1989 – not by choice, but by order. At the time, I was a United States Marine serving my duty in the Philippines, doing all the things a good Marine likes doing: “swinging through the jungle with my M16” as the running cadence goes. I had joined the Marine Corps late in life. I was 24 years old when I enlisted, having worked almost 10 years in a motorcycle dealership up until that point. I had also been racing motorcycles from the time I was 8 years old. To this day, I still have the first trophy I won when I was 10 in 1974. But now I was going to be attending a Motorcycle Safety Foundation course whether I wanted to or not.

As it turned out, a friend of mine with whom I went to high school was commissioned as a Marine Corps officer several years prior to my enlisting. He’d heard through a mutual friend that I had enlisted in the Marine Corps, and he began the search to find me and bring me back stateside because he was looking for an instructor to take over the United States Marine Corps combat motorcycle operators program. He knew me well, and he knew that I had spent the majority of my life working in motorcycle dealerships and racing motorcycles, so he figured I would be a good candidate.

He found me and had orders cut for me to report. I didn’t want to do it. I remember telling my commanding officer that I was not interested in this job. But as you might expect, that argument didn’t end in my favor, and the next day I was on a plane back to the U.S. to meet with the Commanding Officer of the First Marine Division, Division Schools. It was a move that would have profound implications for the rest of my life.

After returning to Camp Pendleton and reporting as ordered, I was transferred to the location where the combat motorcycle operators course was taking place. There were already a couple of Marines there who had part-time jobs teaching Marines how to ride off-road motorcycles for tactical reconnaissance. The current program started with a Motorcycle Safety Foundation Motorcycle Rider Course, and in order to teach that course you had to be an MSF instructor, which I was not. Another way out, I thought. Not so fast—I was off to become a Motorcycle Safety Foundation instructor shortly thereafter.

In those days, there wasn’t anything that was truly formal about the combat motorcycle operators course other than the MSF Motorcycle Rider Course. After that, everything was off-the-cuff and done however the guy there that day felt like doing it. The Marine Corps wanted this course to be more formalized and that was my new job. The problem was that no Staff NCO anywhere on Camp Pendleton would take me seriously, so I struggled to get anything I needed—from corpsmen to provide medical support, to parts, to the time of day. As soon as they found out I had anything to do with motorcycle operations, I was quickly kicked out of their office. Along with my assistant instructor, I taught a few classes, but nothing was ever taken seriously—that is, until August 1991, when Iraq invaded Kuwait.

I didn’t know it when I was struggling for support back at Camp Pendleton, but it turned out that the Chief of Staff of the First Marine Division was a huge motocross enthusiast and fan of everything motorcycles. He was the one behind the push for combat motorcycle operators in the Marine Corps, and I would report directly to him in Saudi Arabia. After I arrived, my orders were to immediately begin training combat motorcycle operators.

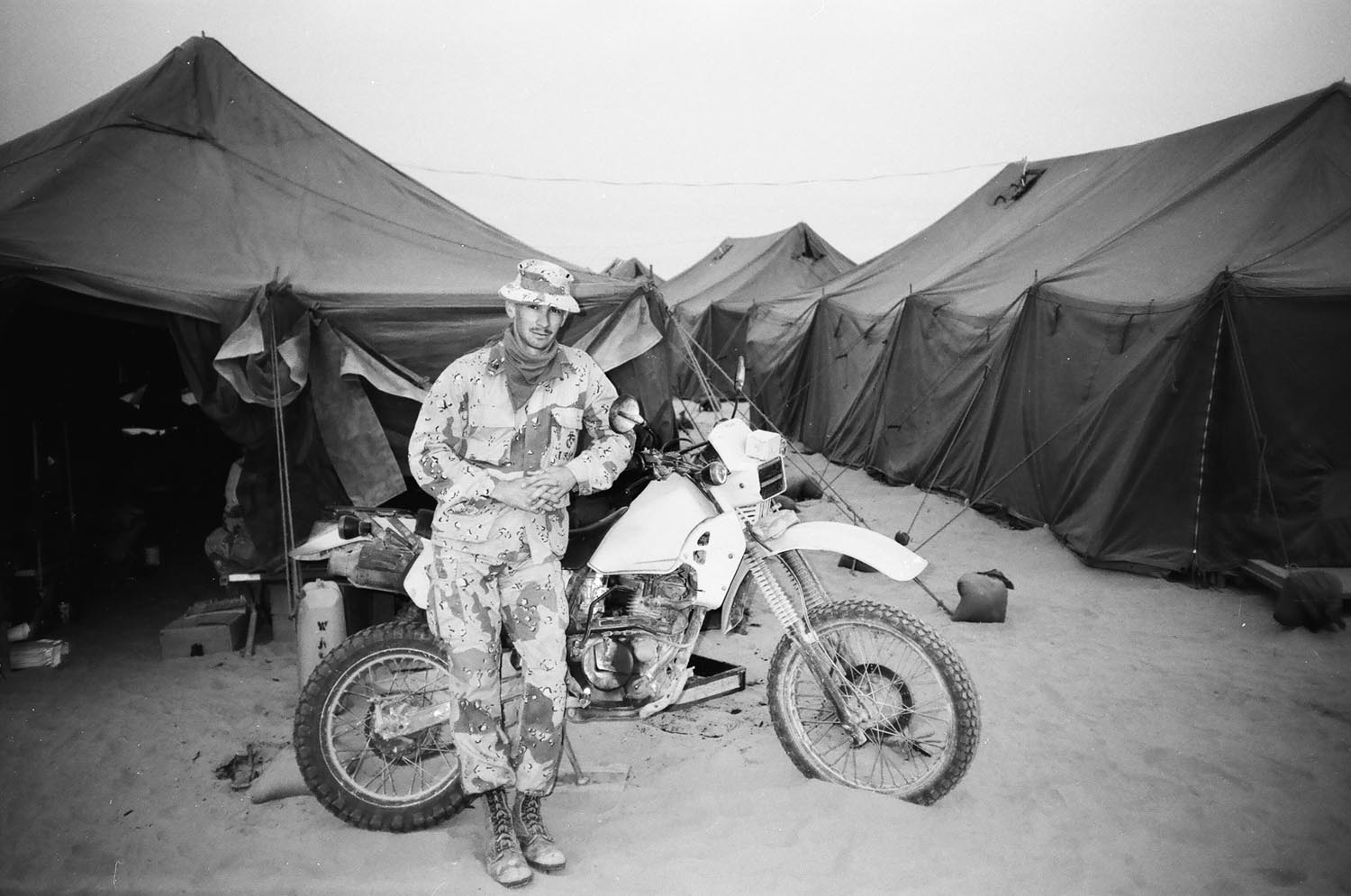

Now keep in mind, we were in the middle of the Saudi Arabian desert—not exactly the easiest place to teach a new rider how to ride a motorcycle. Students were arriving, but they weren’t my normal Marine Corps students; there were British Royal Marines, there were U.S. Army Special Forces—there were even some guys in civvies who wouldn’t tell me who they worked for. Everyone you can imagine was showing up to become a combat motorcycle operator. Suddenly, I was important. On January 16, when the war started, I was assigned to be an actual combat motorcycle operator in a theater of operation. I, along with 15 other Marines, became the commanding officers’ personal go-to guys for everything from sniper insertion to route reconnaissance to forward observation to messenger service. The Commanding Officer proved what he knew was true: Motorcycles could be used in a combat theater very effectively.

After the war ended and we returned stateside, things sped up for Combat Motorcycles. The Motorcycle Safety Foundation, along with the Specialty Vehicle Institute of America, were tasked with assisting us in developing a formal combat motorcycle operators course. That course would later come to be known as MILMO, Military Motorcycle Operators. My enlistment in the Marine Corps was coming to an end, but it wouldn’t be the end of my relationship with the Motorcycle Safety Foundation.

I wanted to finish my college degree, but I needed a job to supplement the GI Bill so that I could make ends meet. I moved down to San Diego and met with the owner of the Academy of Motorcycle Training, who already knew who I was due to my work with the MILMO program. She quickly hired me to be an MSF instructor for her company. At that time, the Academy of Motorcycle Training controlled all of the MSF ranges in San Diego County. They also had the contract to teach MSF courses at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center – 29 Palms.

It was a busy place, and classes ran seemingly nonstop. On the weekends I would teach a range session on Saturday morning, and another one on Saturday afternoon, then again on Sunday morning, and on Sunday afternoon. As I became more seasoned with teaching civilians, I was put in charge of all classroom operations and began teaching on Wednesday and Thursday nights to an audience of up to 100 students who would all attend classroom in one location and then disperse to the various ranges on the weekends.

I did this for about two years while I worked on my college degree. As you can imagine, teaching that many classes without having much of a break and going to school full-time will wear you out. So I started looking for another job in the motorcycle industry and was lucky to land my first real industry job with Shoei Safety Helmet Corporation. I moved to Los Angeles, and soon my career in the powersports industry was off to a great start. I spent two years at Shoei and then was hired at American Honda, where I spent the next 25 years, ultimately retiring as the manager of Experiential Marketing. I’m still involved in the powersports industry as a contributing editor for Cycle News Magazine, where I travel the world riding and writing about new motorcycles. Had I not become a Motorcycle Safety Foundation instructor all those years ago, I’m certain that my life on two wheels would never have turned out so wonderful.